The approach to Guangzhou is spectacular. Looking down on it at night you can see the Pearl River snaking through the heart of the city, edged with green and orange lights. The rest of the city is a blaze of different colours, while the many skyscrapers throw needles of light up into the night sky. Guangzhou is the capital of Guangdong, otherwise known as Canton. Here they speak Cantonese rather than Mandarin and their cuisine is one of China’s four main cuisine styles. For a long time Guangzhou was the only port from where goods were exported from China and imported into the country. The Cantonese also settled in many other countries around the world. Most Chinese restaurants in other countries are actually Cantonese and every Chinatown is also Cantonese rather than Mandarin. The city has grown rapidly in recent years, partly on the back of Hong Kong’s success and also because nearby Shenzhen was mainland China’s first special economic zone. Hong Kong is just two and a half hours away by jet catamaran and three hours by coach.

At dinner I am just about to sip my tea when I'm told that in Guangzhou everyone washes their chopsticks in the tea first, then uses it to wash out the soup/rice bowl before tipping the tea into a large bowl in the centre. I have never come across this particular ritual before. The meal includes camel meat, fish heads and duck blood. I smile and tuck in, hiding my true feelings. The dinner conversation turns to SARS. The city is where it first appeared, and there are stills signs of it with warning notices in hotels, shopts, at the airport and on buses, and people wearing face masks in the street.

One of the first things I notice is the lack of bicycles in Guangzhou. It sets me wondering. Were the people here so affluent they could afford to drive everywhere, or was the public transport system so effective they didn’t need to use them? Or was it just a case that there was so much traffic riding a bike was positively suicidal. I settle on a combination of all three. There are several hotels clustered together where we are staying, and a lot of designer clothes shops either already open or due to open. The area seems awash with money. Brand new BMWs, Mercedes and upmarket Japanese cars litter the car park and fill the roads in the area. There are also a lot of beggars, some very insistent and stopping directly in front of you with their begging bowls and tugging at your arms as you walk past. I buy some noodles for a beggar that night while in a convenience store. I much prefer to do that than give them money. At least I know where the money is going then.

The apartments in the city centre fascinate me. They all have bars over their windows, balconies and conservatories, some of which are very ornate. To me they look like a collection of bird cages piled on top of one another, and I call them bird-cage apartments. The illusion is enhanced by the many pot plants and flowers spilling over the balconies and through the bars. I listen out for the sounds of birds singing but hear only the roar of traffic and occasional horn.

The city centre streets are full of shops. Beijing Lu is traffic-free and lined with pulsating neon signs, clothes stores, electronic and electrical shops and fast-food outlets. There are a couple of areas of the road with glass viewing screens so you can look down to preserved sections of old roads dating back to the Song Dynasty. We head to a nearby snooker hall where I am challenged to a couple of games, both of which I lose on the black ball, although I get my revenge next day. The Chinese are mad about snooker, and there are portraits of stars like Ronnie O’Sullivan, Jimmy White and Stephen Hendry up the stairs and around the hall. There are said to be many up and coming good snooker players in China who will make a big impact on the game. Watching some of the other players in the hall I can well believe it.

We have dinner one night at a restaurant in an area called Saigon, overlooking the Pearl River. It specialises in seafood and has a “live menu” in bowls outside the front including lobsters and crayfish, as well as cages containing chickens, pheasants, partridges and a sad-looking rabbit which I hope won’t end up on our dinner plates. It doesn’t, but the crayfish aren’t so lucky. The restaurant is near a suspension bridge, the cable support towers of which look like a pair of giant crayfish standing on their tails holding up the guy wires. Every so often a river cruise boat comes past in a blaze of blue, red and silver neon, the lights shimmering off the waves. Another couple of nights we eat at branches of the Dong Bei Ren Home-Style Jaozi Restaurant, or Northeast folk dumpling restaurant, part of a chain of serving traditional northeast cuisine and decorated in bright reds and oranges. We are sung a welcome by the staff, all of whom are from that region and dress in traditional Manchurian costume. Their white complexion and vivid dresses make some of the waitresses look like giant China dolls.

We go to the tea market in Fangcun. I can’t believe the number of tea shops or the amount of tea they each contain. No wonder people use the phrase "for all the tea in China" – there's obviously mountains of the stuff. Then we head to Shamian Dao, or Shamian Island, which was the only area were Europeans were allowed to live in the early 1800s. It has lovely avenues of mature trees with squares where people are playing badminton, and lots of colonial buildings reminiscent of London's South Kensington. Across the main road is the Chinese herb and spice market, or Peaceful Market. Guangzhou is known as the city where people eat anything, and this market underlines that. One shop has a giant stoneware vat on the floor and lots of glass jars on the shelves with what look like pickled animals or bits of animals in them. I stop for a closer look and notice some pickled shrimps in one jar but fail to recognise what is in the next one, until Lillian, my interpreter, points out that it is a baby deer. I had missed it first of all because its body and legs were all squashed up, and its neck and head twisted round grotesquely. The market traders seem very reticent to talk to me on camera or let me photograph them or their stalls. I had read that the market has been raided by police in recent years in attempts to stop the illegal trade in rare and endangered animals and their parts. Were these people worried I might find something illicit, or that they might be filmed selling illegal items?

My eye is caught by bags full of seahorses and starfish on one stall. Next to the seahorses are a number of bats on skewers, their tiny legs and wings outstretched like furry little kites. They remind me of the Monty Python cinema sketch where the ice cream seller is selling albatrosses and gannets on a stick. Also on the stall are what look like bags full of cockroaches and a black powdery substance. I discover it is thousands of little black ants, and the thought of eating or drinking a potion made from either of them sends a shiver of revulsion down my spine. I spot several boxes decorated with pictures of swallows, next to which are the nests from which birds nest soup is made. On another stall I see what I take to be small sliced mushrooms but which are in fact thin slices of deer antler, and there are turtle shells hanging up. They are good for your joints, apparently. A couple of days later a local paper has a report about a Guangzhou inhabitant who is just about to chop up a live turtle with a meat cleaver when it cries out, and he is so struck with remorse he decides to take it back into the mountains and let it go. It’s good at least some people have a conscience when it comes to these creatures. I also see bundles of what appear to be small sticks but turn out to be centipedes or millipedes. I’m glad I didn’t meet them when they were alive. The final stall where we film is full of everything to do with deer, including full-size antlers. The stallholder shows me the remnants of the lower parts of deer legs, with the nails of the animals’ hooves still in place. She then shows me another box, giggling sheepishly as she opens it. Lillian translates that it is deer testicles. They are rather shrivelled and attached to a long dried thing which leaves little to the imagination. I am told that not only is it good for your health but is also a sort of long-term liquid Viagra. You mix it up with about 12 or 13 other ingredients – mostly bits of other animals plus some herbs – and it helps to revitalise your sex life. I thank the girl for sharing the information and showing me her wares, but add that I don’t need it. As we walk out of the market I suppress a chuckle over the fact that deer’s testicles help your sex life when you are stuck in a rut!

Along the front of the market people are sorting through a pile of seahorses

on the floor in front of a stall which has sacks full of them. There must be

tens of thousands of them just in this one shop. The mind boggles at how many

must be killed each year to satisfy the demand for medicinal potions. For a

living thing of such delicate beauty to be reduced to these lifeless ingredients

for man’s vanity or superstition strikes me as obscene, despite my pledge that I

would not impose my own Western ideals on what I found in China and the fact

that they are probably farmed in special fisheries. As we walk away from the

market I wonder how many of the countless animals being sold whole or piecemeal

have been taken from the wild, and how many are rare or endangered? I also

wonder whether anyone cares. Thankfully a rally we come across the next day in

the central area of the main shopping street, Shang Xia Jiu Lu, answers my

question emphatically. Posters lining the street proclaim environmental slogans

and warning that the killing of endangered animals will carry on as long as

people carry on buying things made from them while speakers advocate

environmental messages from a large stage. It is gratifying to see this kind of

public awareness in a city with such a notorious ecological reputation.

Wuxi is also home to the CCTV Film and TV Studio, China’s version of Universal Studios. A number of Chinese films and TV series have been filmed here. Like its American counterparts, this complex is divided into zones. We watch a live show featuring a flying kung fu fight sequence in one of them. The show itself is entertaining and funny at times - intentionally so, I think. The aerial scenes could have come from any Chinese martial arts film, with the hero, heroine and baddie locking sword blades, somersaulting and spinning, then leaping past each other in thin air while brandishing their swords. All of it on cables suspended high above the ground and positioned with pulleys and wires by unseen helpers. It only needed Jackie Chan to make it feel like being in the front row of a cinema. Another show features two opposing armies clashing in an arena with lots of high-speed acrobatics and weapon-flailing on horseback.

We board another boat in picturesque Turtle's Head Park and set sail on Taihu Lake. Actually I have to set the sails. It is a replica of a three-masted fishing junk and I am roped into hoisting up the expansive mainsail for the cameras. I then have to don a fisherman's garb of coolie hat and palm frond cape so I can be filmed manning the helm. Except that it is fake. The real ship's wheel is in the aft wheelhouse, and with lots of barge traffic heading for Wuxi and the Grand Canal to avoid I'm sure they wouldn't let me touch that with a barge pole.

One of Jiangsu's most amazing sights is the 88m tall Lingshan Buddha, further round the lake in the Lingshan Buddhist resort . It is the tallest bronze Buddha statue in the world, but that is not what we go there to see. Ethereal music is wafting through the air, and after convincing a jobsworth guard we are there legitimately we race in the opposite direction to the statue. A crowd is transfixed by a huge bronze column in a marble-edged pond, the top of the column shaped like a giant lotus flower. Its petals are slowly opening to reveal a shiny bronze statue of a young Buddha, small by comparison to the main statue but still 7.2m high. As the leaves continue to open the statue slowly revolves. Fountains dance around the base of the bronze lotus, and as the music rises to a crescendo water jets spout from the mouths of nine bronze dragons set around the pond’s perimeter. They douse the figure, now fully revealed, in a scene meant to symbolise Buddha’s birth. Once it has completed a full circle, the little Buddha retreats back inside the petals until it is once again hidden from view. The fountains abate and the crowd melts away, the bizarre but powerful spectacle over until the next day. Everything in Lingshan is on an immense scale, but we are in a rush so have no time to see the giant statue or any of the other sights which have attracted 10 million visitors since the resort opened seven years ago. We miss the 1,000-year-old Xiangfu Temple, likewise the biggest bell south of the Yangtze River, the biggest tripod urn in China, the largest bronze palm – hand, not tree – in the world and the Museum of Buddhist Culture.

Yixing is famous for its purple clay teapots. They have been made in the town since the Ming Dynasty and the many artists drawn there over the centuries have helped turn the humble teapot into a highly-prized work of art. Examples by noted artists can fetch tens of thousands of dollars. At the ceramics workshop of master potter Xiutang Xu I watch craftsmen hand-making teapots as well as a tableau of lifesize figures in the purple clay, then Mr Xu shows me his magnificent 2.8m sculpture of a warrior figure - the largest sculpture by anyone in the material.

Among Suzhou's many ancient tourist sights is Tiger Hill, which is surmounted by China's very own Leaning Tower. The top of the seven-storey 1,100-year-old brick Cloud Rock Pagoda began tilting 400 years ago and is now more than two metres off centre. But it is the classic Chinese gardens which are the city's main claim to fame, four of them having UNESCO World Heritage status. Hundreds of private gardens were built over the centuries, most by wealthy officials who fell from favour with the imperial court. We film in two, the 500-year-old Humble Administrator's Garden and the tiny but beautiful Master of the Nets Garden. The gardens' creators were aiming to present them as landscape paintings using rockeries and water with bridges, corridors and pavilions. The many doorways, shaped windows and latticed wood supports of the buildings help focus the eyes on particular scenes, creating their own little framed landscapes. Some of the scenery is obvious, other aspects are hidden, the still water creating mirror images of some scenes. The mirror effect is amplified in the Master of the Nets Garden, as we visit at night when the outlines of the pavilions and buildings are brightly illuminated. We are there to watch performances of the local opera, called kunqun, and musical performances called pingtan. I expect to have to sit through hours of shrill, ear-piercing singing. But it is a series of cameo performances, each only about five minutes long. As each one finishes the audience moves off to the next pavilion for the following one. There is traditional opera as well as musical exhibitions of instruments including a piba (like a lute), guzheng (a Chinese plucked zither), sanxian (a three-stringed banjo) and dizi (bamboo flute).

Suzhou is also famed for its silk and embroidery, and at the Suzhou Embroidery Research Institute I watch some girls embroidering large and intricate silk panels stretched out on wooden frames like oversized artists’ easels. One is working on an abstract of vibrant blues and greens which, when finished, would then be sold in the institute’s shop for 100,000 yuan, or over £7,000. It sounds a lot, until I realise that the price represents a year's labour and the institute's mark-up. The most expensive work took three years and is on sale for 240,000 yuan, just over £17,000. Special double-sided panels can only be done by a few masters. There are several examples on show, the patterns different on either side although the outlines must be the same shape. One is of Prince Charles on one side and Diana on the other. Neither looks like the real thing, but I diplomatically praise their likenesses when they are pointed out to me.

I get the chance to try some Chinese as we leave Suzhou. "Women milu le ma?" Or in English: "Are we lost?" The answer is yes. Our driver gets totally lost after stopping by the Grand Canal for us to film and take pictures of all the barges. I am amazed at how incredibly busy it is. The canal is like an aquatic motorway. Instead of the convoys of lorries there is a procession of industrial-age marine beauty queens, each propelled by as many as five or six raucous engines across the stern and all of them belching out plumes of steam and smoke. Barges are mainly used to transport building materials and coal along the Grand Canal. Empty ones sit high above the waterline like paper boats, but the fully-laden ones are so low in the water that it seems as though a single ripple would be enough to flood over the hull and sink them.

In Nanjing we go to what was once the city’s red light district, Fuzi Miao. We have dinner in a former brothel on the bank of the Qinhuai River, and are shown down steep stairs to a terrace overlooking the river where the ladies plied their wares. Dinner consists of 16 courses of local dimsum, called Qinhuai xiaochi, plus six to eight side dishes. The meal reminds me of Noah’s Ark, the dishes coming in two by two. The courses are served in pairs, one dry and one moist. I can’t keep up. Every time I finish one they bring two more, so that I end up with half a dozen in front of me and admit defeat. Alongside a bridge over the river is a screen wall of dragons dating back 500 years, yet the pink and green neon lights decorating it make it look more like a funfair attraction. At least it is in keeping with the rest of the area, which is Nanjing's main amusement zone. Even the Confucian Fuzi Miao temple across a lake by the screen wall looks tacky, the curved outlines of its roofs picked out by strings of lights.

Despite the initial impressions I like Nanjing. It is a clean city with wide roads and a modern heart of soaring offices, hotels and shopping centres. Yet it has managed to preserve much of its rich history. Nanjing is one of China’s six ancient capitals. It was the country’s capital for a time during the Ming Dynasty before the third Ming emperor, Yongle, decamped to Beijing. It was also briefly the capital in the early 20th Century, when the Provisional Republican Government of China which ended the country’s long dynastic era was set up by revolutionary hero Sun Yatsen, regarded as the father of modern China. After his death in 1925 a huge mausoleum complex was built to honour his wish to be buried in Nanjing. Today it is a source of pilgrimage for Chinese and overseas visitors alike, and we go there to film. The tomb is an impressive Ming-style building at the top of a colossal stone stairway of 392 steps, 323m long and 70m wide. Streams of people make their way up the steps to pay respects to China’s revolutionary founder including one group bearing a huge Communist Party flag. I watch and photograph them until the fluttering flag reaches the mighty blue-topped mausoleum at the top.

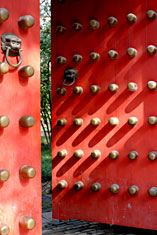

Nanjing was surrounded by one of the longest city walls ever built and two-thirds of its still stands today. We visit the 600-year-old Zhonghua Gate, one of several of the original 13 Ming city gates still standing and regarded as the grandest in China. We walk through the arched gateways below the gate, then up the sweeping ramp past mannequin soldiers standing guard with flags to the grassy expanse at the top where several people are flying kites. We also visit the tomb of Hongwu, the first Ming emperor. Beyond marble bridges swathed in yellow and red flowers a tree-lined avenue leads to a red-walled imperial gate topped by yellow tiles and mythical creatures at the corners. The central arched doorway has two massive, bronze-studded red doors sporting brass lion knockers. The actual tomb is in an as yet unexcavated vault beneath a huge earth mound surrounded by an imposing wall.

Balmy Garden, in the centre of the city, is a classical Ming garden. It housed the opulent Mansion of the Heavenly King, built after the Taiping rebellion in the mid 19th Century on the foundations of a former Ming Dynasty palace. But it burnt down in the fall of the Taiping and what exists now is a reconstruction of some rooms and halls. Some of the buildings were used as the president’s residence and office during the time of Sun Yatsen’s government and again during the Kuomintang rule up to 1949. The tranquillity of the garden is in stark contrast to the violence which surrounded the Taiping. Rebel leader Hong Xiuquan was a religious zealot who, according to the Taiping creed, was the brother of Jesus sent down to earth to exterminate demons personified by the Qing Dynasty. The rebels slaughtered the Manchu population after Nanjing fell, ruling it with a puritanical Christian grip for 11 years. The city was retaken by the Qing army in 1864. None of the 100,000 fanatical Taiping rebels surrendered to the invading force, preferring instead to take their lives in a mass suicide.

We drive to the Yangtze River to film the grandiose Yangtze River Bridge. It is immense when you are up close, the elevated railway towering overhead on giant concrete legs with the roadway above that. A series of rectangular openings at the base of the legs makes it look like a gigantic version of the long, straight corridors in China’s ancient imperial palaces, receding far into the distance. This is monumental Communist architecture at its most impressive. An elevator takes visitors up to the gallery next to one of the river-side piers. The view is fabulous. On the landward side the railway and road come together to form the double-deck bridge, the point where they meet marked by a pair of statues of heroic workers and soldiers on the parapets either side of the roadway. In the other direction the bridge marches across the wide expanse of the Yangtze, a succession of cargo boats of all shapes and sizes plying up and down waters made golden by the misty setting sun.

On our last morning in Nanjing we visit the Brocade Museum and Research Institute. The brocade is silk woven with colourful threads, sometimes even gold and silver. It is one of the most famous brocades in China and dates back some 700 years to the Mongol rule of the Yuan Dynasty. The weaving room is like an industrial revolution era factory in England. A row of large wooden platform looms are operated by two people, one at the bottom and the other sat high up in the leviathan's frame. The lower operators weave the coloured weft threads across the single-coloured warp strands. It looks almost as if they are organists, their feet operating bamboo rods like the pedals of a Wurlitzer and the multi-coloured bobbins laid out in front like organ keys. The weavers can only produce 5-6cm of brocade length a day. As a result it is very expensive. The cheapest ones cost 2,000 yuan, about £145, per metre while ones made with gold or peacock feathers cost up to three times that. It can also only be made by hand, as they have not perfected machine-made brocade yet. I hope they never do. In earlier times it could only be used to make formal imperial robes or casual dress for the emperor or imperial family members, and the weavers were all men as women were regarded as inferior and could not touch the material. Now women can work as weavers and wear the brocade, a point proven by a fashion show of fabulous brocade dresses just for our benefit.

At dinner one night with officials from Jiangsu's tourism bureau my colleagues decide I should have a Chinese name, a tradition for foreigners spending any length of time in the country. They settle on one which they say represents my role as “ambassador” and a cultural bridge between England and China. The name they give me is Pi Ying Hua, which translates literally as Peter England China. It is an honour which makes me feel as though I have been accepted as one of them, instead of being an outsider.

Next stop: Tongli.